Watched this earlier today, got so inspired I thought I'd make two blog posts before turning in.

Standout quote: "Limitation is a core part of any creative project"

...

Agility

The speed at which characters can move, and the grace with which they overcome obstacles that impede their exploration, is the key staggering mechanism to your game's content. Consider D&D: you can't get far in the wilderness at early levels. It's just too damn dangerous; wandering monsters that severely outclass you make travel risky, and this risk isn't weighed against a comparable reward, because *wandering* monsters are *outside* of their lairs, and hence do not grant treasure when slain.

As you gain wealth and competence (and these are linked skillfully by the GP=XP mechanism), you not only gain the ability to overcome, survive or escape the danger of wandering monsters, but you gain access to faster modes of transportation, broadening the range that you can travel safely and swiftly.

This means that a handful of hexes filled with content can be a year's worth of campaigning if you start the game at level 1. All this is because of the difficulty of travel; if the players began with magic carpets and rings of invisibility, they'd range to the limit of your map within the first session because the obstacles of getting lost, attacked by monsters, starving, or other hindrances to their movement like mountains, oceans or swamps would be below their capabilities.

Hence my problems with content pacing in LWF; the Effect chart has "fly at mach 1" within the grasp of any starting character.

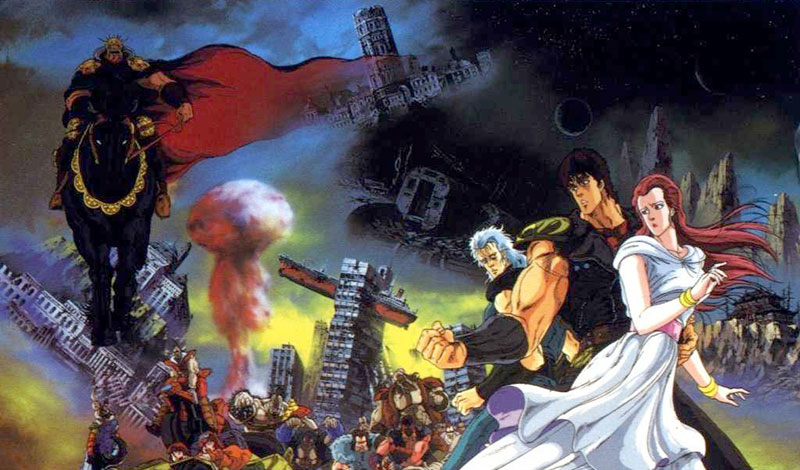

It *needs* to be there: after all, this game aspires to the likes of Dragonball Z and Avatar: the last airbender. If you can hurl a battleship to the moon, you can certainly zip around like Aang or Goku could do from episode 1 of their respective shows.

But, there's more to it than that. You don't need to dig deep to realize that these show's dynamics are fundamentally altered by the freedom of movement enjoyed by the characters.

Take DBZ, which grew out of Dragonball, which grew out of Journey to the west: the Chinese equivalent to the Odyssey. An epic defined by having a very onerous time getting anywhere. Comparing Dragonball to Z, we find that the world of Dragonball is *denser*: Goku and Bulma travel by land, and they're constantly encountering colorful characters, landscapes and situations. DBZ, while technically sharing a world, is emptier; both Earth and Namek are voids of interchangeable wasteland battlefields, nearly abandoned save by the occasional doomed news crew or cookie-cutter Namekian village.

The ease with which character breeze past, over or through the challenges of the previous series is played for laughs; it's become a joke to them because of the scale they're operating at. The content centers on those things which cannot be ignored; the overpowering presence of the Saiyans, or Freeza, or the Androids or Cell or Buu, These things hunt down the characters and wreak havoc unless dealt with; a far cry from the chance meetings and discoveries of the travel-based Dragonball.

Even the ancient authors realized they'd written themselves into a corner with the Handsome Monkey King; directly before his Odyssey, he leaps from five elements peak to the edge of the world and back in the blink of an eye. Then he has to walk at normal, human speed all the way to India.

Wukong is brought down to human scale by his mission; he can't just leap to India, grab the texts, and leap back. It doesn't work that way; his journey forces him to behave as a considerably less capable character, and the narrative is richer for it. Think about it; he effortlessly leaped over his entire life story before living it. Which was the more satisfying journey?

Let's get real though; players don't give a crap about that zen BS. They can jump over a continent and be DAMNED if they don't get to PLAY with their new TOY.

And that's fair; why give the players a power if you don't intend them to use it?

Let's get real though; players don't give a crap about that zen BS. They can jump over a continent and be DAMNED if they don't get to PLAY with their new TOY.

And that's fair; why give the players a power if you don't intend them to use it?

But therein lies the challenge for us as game designers; we're left with climbing that peak. How do you allow Sun Wukong his world-leaping jump, but still make his journey to the west something the player must or wishes to do?

How indeed?

The Scenes

The guiding logic of the redesign again works in my favor here; by cleanly dividing the capabilities of players between the timeframes of scene mechanics, I distinguish a sprint from a run from a journey. I define movement in terms of the length of time taken to move, and the application of a single acrobatic act from the sustained grace of parkour or the incredible agility of the Sherpa*.

*(As an aside, I recently got dinged by one of my more progressive friends for using the term "Sherpa". If you're a member of a Himalayan mountaineering tribe and feel this use to be insulting or an act of cultural appropriation, give me a jingle and I'll replace it with a less offensive term. If you don't care, also tell me that because I'd love to rub that in her face)

I powerfully de-escalated the distances that could be blazed over within Action Scenes, but that went hand-in-hand with defining what I'm going to call the "content-space" of a given area because you. can't. stop. me. Also it feels like it gets the idea across.

So I'm gonna explain it in D&D terms again, because that's how I think about it:

D&D has the ROOM as the basic node of content: we all know what this is. Kick in the door, you enter a new room. Rooms have a key and a little space on the map of your dungeon; they have character, in that there's something written in their key. "3 orcs guard a chest full of 20 GP" is, in essence, the fundamental character of that room. Some rooms are better than others, clearly. Compare my orc chest room with this fiendish masterpiece:

Now that's a room with character. But it's still a room: it's defined within it's walls. The stuff on the key is there, a discrete and distinguishable different piece of content from adjacent rooms. It is our most basic node of content.

I took this logic and broke down it's walls, but kept it's distinguishing elements and created the Field or Battlefield depending on what mood I'm in. By taking this same idea of a discrete place with more-or-less defined boundaries of "no longer that place", you get a dungeon room you can put outside and this is a critical chunk missing for me in almost every game ever made.

So, our single entry, our content node, is a Field.

A collection of joined rooms is a Dungeon in D&D terms. Dungeons are thematically cohesive; they are whole, complete places, more than just the rooms and connections between them but also their location, inhabitants, treasure, even history.

So if collections of rooms are dungeons, collections of Fields are Tracts: recognizable geographic areas of conjoined Fields sharing spacial relationship, theme, location, history, inhabitants (in the form of encounter lists and keyed inhabitants, identical to our dungeon) and the unifying sense of place inherent in rooms to their larger dungeon.

And just like that, we now have a familiar, recognizable and comprehensible structure which allows us to make an above-ground, unenclosed area with the same ease with which we make a firewalled dungeon.

We also now have a means of translating the movement of characters into a recognizable pacing mechanism; that of walls and doors, traps and obstacles. Cunning D&D players traverse such things, but need special permission (lockpicks, battering rams, makeshift bridges, rope) and risk danger or detection when moving between rooms. So to, do we place surrounding dangers; fortified buildings, rushing rivers of toxic filth, barbed wire, minefields, the concrete and steel innards of a shattered urbanscape, etc. Players similarly overcome them with either acrobatics or ingenuity.

What happens when we adjoin two or more dungeons to one another? We craft the epic, multi-tiered play space of a Megadungeon; shifting between it's enormous layers changes the character and danger level of what we encounter. So to, do I group together Tracts into the overarching above-world megadungeons of Domains.

Suicide Heaven, haunted demon-city of the Shadow Vipers, is one such open-air megadungeon, as is the glistening half-drowned demi-utopia of the Silver Phoenix and the savage cradle of primordial jungle inhabited by the ferocious Emerald Kirin. These aren't just "places you go", they're entire campaign arcs, possible whole campaigns worth of adventure, challenge, danger, and treasure. Wars could rage within their boundaries and still be unencountered by the players.

D&D gets bigger, though, than megadungeons; because even the most colossal of these is well-contained within a single hex on the map of your world. So to, do I define Regions; these are those neighboring places, vast expanses between cities, towns, forests and dungeons where the entire character of the game alters.

And now we have three broad cataegories of action in regards to movement: getting stuck in ("not moving"), choosing a new place in which to get stuck in ("traveling") and getting side-tracked, delayed or thwarted in your attempts to choose a new place ("dealing with an encounter/obstacle")

Additionally, we have a better grasp of what the prep for a given place will require of us as GMs. If you're going to embark on a year-long campaign, you should probably prep a Domain's worth of content (one "megadungeon"). If you just need an evening's entertainment, a small but densely populated Tract should get you through (a "five-room Dungeon" will suffice).

That also gives me a compass for what the movement rules should allow. Check it out.

*(As an aside, I recently got dinged by one of my more progressive friends for using the term "Sherpa". If you're a member of a Himalayan mountaineering tribe and feel this use to be insulting or an act of cultural appropriation, give me a jingle and I'll replace it with a less offensive term. If you don't care, also tell me that because I'd love to rub that in her face)

I powerfully de-escalated the distances that could be blazed over within Action Scenes, but that went hand-in-hand with defining what I'm going to call the "content-space" of a given area because you. can't. stop. me. Also it feels like it gets the idea across.

So I'm gonna explain it in D&D terms again, because that's how I think about it:

D&D has the ROOM as the basic node of content: we all know what this is. Kick in the door, you enter a new room. Rooms have a key and a little space on the map of your dungeon; they have character, in that there's something written in their key. "3 orcs guard a chest full of 20 GP" is, in essence, the fundamental character of that room. Some rooms are better than others, clearly. Compare my orc chest room with this fiendish masterpiece:

Now that's a room with character. But it's still a room: it's defined within it's walls. The stuff on the key is there, a discrete and distinguishable different piece of content from adjacent rooms. It is our most basic node of content.

I took this logic and broke down it's walls, but kept it's distinguishing elements and created the Field or Battlefield depending on what mood I'm in. By taking this same idea of a discrete place with more-or-less defined boundaries of "no longer that place", you get a dungeon room you can put outside and this is a critical chunk missing for me in almost every game ever made.

So, our single entry, our content node, is a Field.

A collection of joined rooms is a Dungeon in D&D terms. Dungeons are thematically cohesive; they are whole, complete places, more than just the rooms and connections between them but also their location, inhabitants, treasure, even history.

So if collections of rooms are dungeons, collections of Fields are Tracts: recognizable geographic areas of conjoined Fields sharing spacial relationship, theme, location, history, inhabitants (in the form of encounter lists and keyed inhabitants, identical to our dungeon) and the unifying sense of place inherent in rooms to their larger dungeon.

And just like that, we now have a familiar, recognizable and comprehensible structure which allows us to make an above-ground, unenclosed area with the same ease with which we make a firewalled dungeon.

We also now have a means of translating the movement of characters into a recognizable pacing mechanism; that of walls and doors, traps and obstacles. Cunning D&D players traverse such things, but need special permission (lockpicks, battering rams, makeshift bridges, rope) and risk danger or detection when moving between rooms. So to, do we place surrounding dangers; fortified buildings, rushing rivers of toxic filth, barbed wire, minefields, the concrete and steel innards of a shattered urbanscape, etc. Players similarly overcome them with either acrobatics or ingenuity.

What happens when we adjoin two or more dungeons to one another? We craft the epic, multi-tiered play space of a Megadungeon; shifting between it's enormous layers changes the character and danger level of what we encounter. So to, do I group together Tracts into the overarching above-world megadungeons of Domains.

Suicide Heaven, haunted demon-city of the Shadow Vipers, is one such open-air megadungeon, as is the glistening half-drowned demi-utopia of the Silver Phoenix and the savage cradle of primordial jungle inhabited by the ferocious Emerald Kirin. These aren't just "places you go", they're entire campaign arcs, possible whole campaigns worth of adventure, challenge, danger, and treasure. Wars could rage within their boundaries and still be unencountered by the players.

D&D gets bigger, though, than megadungeons; because even the most colossal of these is well-contained within a single hex on the map of your world. So to, do I define Regions; these are those neighboring places, vast expanses between cities, towns, forests and dungeons where the entire character of the game alters.

And now we have three broad cataegories of action in regards to movement: getting stuck in ("not moving"), choosing a new place in which to get stuck in ("traveling") and getting side-tracked, delayed or thwarted in your attempts to choose a new place ("dealing with an encounter/obstacle")

Additionally, we have a better grasp of what the prep for a given place will require of us as GMs. If you're going to embark on a year-long campaign, you should probably prep a Domain's worth of content (one "megadungeon"). If you just need an evening's entertainment, a small but densely populated Tract should get you through (a "five-room Dungeon" will suffice).

That also gives me a compass for what the movement rules should allow. Check it out.

Action

The skill of coordination, reflexes and speed allows characters to Traverse difficult and dangerous terrain, allowing new interactions with the environment. It also grants them a burst of Speed, allowing them to dash across vast distances in a single moment.

For Traversing challenging terrain, Reference the Agility Effect Chart to determine whether a given movement action possesses enough reflexes and grace to move over a given obstacle or terrain, or pull off a method of movement (such as spider-climbing or rope-walking) that allows a novel form of movement unavailable to less dexterous characters.

For bursts of Speed, reference the Dynamic Movement Chart for Real-Time scenes below.

Dynamic movement

Moving vertically and jumping large distances is part and parcel of the kung-fu heroes in this game. When characters need to push themselves to incredible levels of mobility with an Agility action, consult this chart to see how far they go.

0-Normal human movement and agility. You can jump 3’ (1 meter) vertically or twice that horizontally without significant effort. You move fast and far enough to maneuver within or across a single Field during your turn. You begin your next turn in any adjacent Field.

1-Superior human athletics. With significant effort, you can leap 6’ (2 meters) vertically or four times that length horizontally. This allows you to bound over significant obstacles. You’re fast enough to move through a Field and into an adjacent one during your turn; you can split your other actions between things in either Field.

2-Olympian effort. Your exceptional prowess allows you to leap 12’ (4 meters) vertically or 18’ (6 meters) horizontally. This is enough to scale buildings in a few bounds. You can move through two Fields and maneuver within a third with this incredible speed.

3-Beyond-human athletics. Achieving this rank, you can leap several stories in a bound. This allows you to cleanly traverse most obstacles at a whim. You can move through three Fields and maneuver within the fourth with this speed. Alternatively, you may maneuver within or across a single Tract during your turn. You begin your next turn in any adjacent Tract.

4-Superhuman movement. This rank lets you leaps tall buildings in a single bound. You can move through four Fields and maneuver within the fifth with this speed. Alternatively, you can move through a Tract, emerging in an adjacent one, splitting your turn’s actions between them as you desire.

5-Titanic stride. This speed allows a character to streak across Seven Fields in a single instant. Alternatively, you can move across two Tracts and maneuver in a third.

6-Small god’s motion. With this divine flight, you may traverse three Tracts and maneuver within the fourth. Alternatively, you may maneuver within or across a single Domain during your turn. You begin your next turn in any adjacent Domain.

7-Herculean heft. Four Tracts may be traversed with this blinding burst of speed, moving freely through the fifth. Alternatively, you may burn across one Domain and enter a second with this bullet-quick flight, splitting your turn between them.

8-Deific bound. You sear across seven tracts in a display of godlike alacrity. This is alternatively fast enough to cross two Domains and enter a third.

...

Note the design on Rank 6; this is the ceiling for characters lacking movement-extending magic, so acts as a good predictor of what a party (rather than a single vulnerable starting character) can do in terms of free movement choices. Barring extraordinary circumstance, it acts like a D&D spell which grants you instantaneous transportation into a neighboring Megadungon that shares walls with your current one.

This is still a *lot* of power and freedom in the hands of a starting party; but it's significantly easier for a fledgling GM to turn to a different content-section of the book and simply start running the new area. It's also a significant drain on a new character's resources; a Rank 6 action isn't tenable until the later stages of combat, or alternatively leaves a character stranded in a new area and totally depleted of Prana; effectively trading a more reliable combat strategy for a desperate retreat.

...

Real-Time

Dodging

The most basic of all uses for speed and coordination; getting the hell out of the way. A sister to the Endurance mechanics, dodging allows you to avoid incoming dangers rather than shrug them off. Reference the Agility Effect Chart to get an idea of how speedy a danger you can avoid with your wits and reflexes.

Some areas can only be safely traversed by sustaining a Dodge action as you move through them. The Rank of this action is derived from the Agility Effect Chart. Characters finding themselves within such an area and unable to dodge suffer its consequences (such as being cut apart by dancing lasers or a hail of broken glass).

These dangers might manifest as an attack, a Hazard, or some more esoteric thing (failing to dodge a storm of flying prayer strips might result in a curse, for example).

Flee and pursuit

How does one escape a sufficiently dedicated foe? Certainly you wouldn’t flee a fight you’re winning; if you’re running, you’ve already realized that you’re at a disadvantage. But if your foe has the advantage, how can you hope to escape?

Simple; you make pursuit harder for them than fleeing is for you.

Characters who opt to flee during their turn move as per the Dynamic Movement Chart. Additionally, they leave behind a either a trail of hastily created traps as they knock over the terrain behind them, or a twisting, confusing pattern of escape that makes them difficult to track.

Because of these tactics, fleeing characters may leave behind difficult terrain equal to (their Agility action to flee -1 Rank) or they may hide themselves, which grants them (Agility action to flee -1 Rank Senses) as a sustained hiding action.

Acrobatics and parkour

Some areas cannot be moved through freely; either because the ground is slick or unstable, or because there’s no ground at all (in the case of balancing acts on power lines or defying gravity by fistfighting on the side of a speeding train).

In such cases, a sustained agility action of appropriate Rank must be used to allow the character the ability to move and maneuver normally on the terrain. Consult the Agility Effect chart to determine the fantastic gravity-defying feats required for such challenging footwork.

....

You're seeing some playtest feedback here. We had a scene occur where a player entered an area that required constant dodging from danger. The ad-hoc rule that was used to simulate that (a sustained Agility action) was more formally adopted within the text, since it gave an outstanding guideline. There's also a wrinkle added by myself; I got tired of running away being a non-option in Legends of

the Wulin, so I made an explicit rule encouraging it. It also leads to flee and pursuit being a re-contextualizing of a continuing combat, which is fun.

.....

You're seeing some playtest feedback here. We had a scene occur where a player entered an area that required constant dodging from danger. The ad-hoc rule that was used to simulate that (a sustained Agility action) was more formally adopted within the text, since it gave an outstanding guideline. There's also a wrinkle added by myself; I got tired of running away being a non-option in Legends of

the Wulin, so I made an explicit rule encouraging it. It also leads to flee and pursuit being a re-contextualizing of a continuing combat, which is fun.

.....

Montage

Considering the blazing speed and mindblowing acrobatics with which character might move in this game, one naturally asks: “What’s left for Montage scenes?”

Recall that the essence of the Agility skill is movement, and the essence of Montage scenes is sustained or repeated use of a skill. Considering these two together, we’re left with that most fundamental of long-term movements, travel.

Travel

The World of Ashes and Ghosts is vast. So vast that even the ancients, before their disastrous fall, spread uncountable leagues of glass and concrete tunnels below the world to connect it’s disparate cities and lonesome temples. Now, the poisonous stretches of wasteland act as barrier in their distance alone, keeping the scattered clutches of humanity separated by their impassable length.

When embarking on a journey, the Rank of Agility required to successfully reach one’s destination is judged by two factors: The Distance of the journey, and the difficulty of traversy the intervening Terrain. Consult the Journey chart below to determine the Rank required: simply add the Distance attempted to the most difficult Terrain encountered en route.

Journey Chart

Distance

0- Fields

1- Tracts

2- Domains

3- Regions

Terrain

0- Smooth and level terrain (roads)

1- Bumpy and broken terrain (unworked earth, hardpack)

2- Resistant, slick, or sticky terrain (marsh, mud, loose sand)

3- Dangerous, shattered or dense terrain (cliffs, jungles, broken lands)

4- Precarious or deadly terrain (mountainsides, minefields, quicksand)

5+ - Barriers or impassable terrain (fortress walls, chasms, oceans)

How far do you go?

Note that when you travel, there’s not a number of areas traversed; simply a category. This is because of the nature of travel; namely, how boring it is. That’s why we’re skipping over it with Montage scenes!

That’s the purpose of travel rules; to get through the tiresome scenes of walking while nothing happens as painlessly as possible. However, this also means that travel, by definition, ends when something interesting starts happening.

This is a two-edged sword: one the one edge, you want to go as far as you can during your precious Montage. On the other, “interesting things happen” is the entire reason you’re playing the game.

So, while traveling, after you move into each new area (Tract or Domain or whatever), roll for Orthogonal Content in that area. If the roll results in an encounter, it interrupts the Montage as normal and you have to resolve the scene before you can return to traveling. Of course, you can choose to stop traveling and get involved in whatever adventure is promised by the new content, but that’s your call.

.....

I think I'm going to adopt that "roll an encounter when you cross a boundary" rule

to the faster travel of Action scenes too. It seems a bit inconsistent as it's written. Good note.

I think I'm going to adopt that "roll an encounter when you cross a boundary" rule

to the faster travel of Action scenes too. It seems a bit inconsistent as it's written. Good note.

.jpg)