Without further ado:

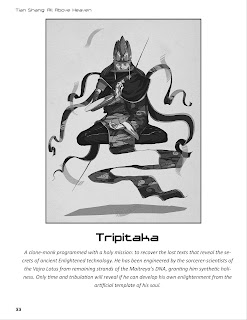

Lores start out like your typical "splat"; they give you a broad-scale overview of the in-universe thing it represents (in this case the Varja Lotus, Tripitaka's brotherhood of "I can't believe they're not Buddhists!"). I also threw in a bit afterwards giving you some reasons why you'd include the lore in your game or as part of a character, because that saves you having to read the whole damn lore if the thesis doesn't grab you.

Lores are the key to advancing in this game: they're the training manuals, wizened masters and martial brotherhoods that offer training in the fighting arts. I wanted to make certain that the advancement mechanics were rooted in the in-genre conceits of Wuxia and Shonen; if you got stronger, its because you trained, and if you learned a new move, its because someone taught you.

If you want to purchase a new Siddhi, Gupt Kala, or Skill Mastery, you've got to get it from an organization you've entangled yourself with. There's another mechanic, not present on this sheet but in the works, which directly tracks how much favor you've curried with an organization, and this determines what they're willing to teach you (as a base; individual masters are almost always eccentric weirdos, but that's for you to roleplay, not the rules to dictate)

The Lotus offer three Masteries, I suspect most organizations will offer a similar amount. Spirit is the real keystone to the martial arts and shadow arts that they teach, so if you take this Lore it's what I'd recommend for your first choice. Spirit mastery also gives you +1 rank to open a Chakra, which is crazy powerful.

Finally, you get to see some of the Siddhis in their signature martial art style. I learned when writing them that their formatting follows the formatting of charms in Exalted very closely! It wasn't intentional, but if you're familiar with that game then you'll note the similarity right away. I guess those guys knew what they were doing.

The martial arts template I devised is separated into 4 tiers: Novice (beginning techniques taught to amateurs), Expert (More powerful techniques for your "established" kung-fu badasses), Master (Which is what your wizened masters use to whup your butt), and Ultimate, which is the cherry of the asskick cake.

(David specifically requested the giant-golden-hand-of-god attack; I made it an homage to kung-fu hustle because how could I resist?)

So let's talk about Siddhi

The Name is pretty self-explanatory. In a noteable divergence from Exalted, people in the Galaxy above Heaven actually use the crazy over-the-top names and recognize that they're using their magic to cast kung-fu spells.

The Rank is worthy of mention; it's the amount your base roll is increased in increments of ten. So like, if it's rank 1, that's +10. Rank 3 is +30. This helped to keep our math as single-digit as possible, which considering how much you have to track was a major boon.

Facings deserves some explanation as well. When you roll your Effort pool (a big ol' pile of d10s), the numbers you generate are the Facings of the dice. Siddhis only generate "dice" of certain facings; in the case of say, Maitreya's Palm, this is any Facing between 6-8.

What this means is that you can boost dice sets you've rolled in your Effort pool or stored in your Focus slots, but only if they have the right Facing.

On the other hand, you can just straight-up generate an action if you want. Using a Siddhi isn't any different, rules-wise, from just rolling a set, or constructing one from your Focus dice. So if you just want to burn through your magic go-go juice, you can shoot all the eyebeams you can afford. Speaking of which....

Cost is the amount of Prana it takes to use the Siddhi. Nothing much to explain there.

Power is the meat of the Siddhi. It describes the mechanical effect and restrictions of the technique. There are some keywords, because certain rules have juuuust enough text and appear in juuuuust enough techniques that keywords are a no-brainer option. Offensive can only be used to attack, Defensive only for defense, to give an example.

Arik suggested that, in addition to the more-or-less linear power scalar that more powerful Siddhi introduce, we focus on interesting "rider effects" that broaden the scope of what can be accomplished with magical punches. I loved the idea, so there's a ton of cool stuff that Siddhi do apart from just throw Hadokens back and forth.

(Actually wait, did it work like that? I've been eyeball-deep in designing this game for so long, I might be misremembering how LotW handled this)

I didn't dare try to recreate the genius which was the secret arts section of Legends of the Wulin; that part of the game is basically perfect, all I could do would be make a watered-down version. So I came at the shadow arts or Gupt Kala from a different angle, treating them more like martial arts styles instead of a set of general principles that practitioners mastered.

Treating them like this had the upswing that I didn't have to reinvent the wheel as far as learning new moves was concerned; go back to your master or seek out a new one and learn some new techniques, just the same as Siddhi.

Because LotW and WotG didn't concern themselves mechanically with locations (which Tian Shang does with battlefields, elements, the tactical infinity, and the effect chart) there wasn't much emphasis on detailing locations like strongholds or interesting features of the scenery.

This was a much bigger issue in WotG; the descriptions of places are airy and insubstantial, couched in flowering, poetic language that's just this side of worthless on a game table. Legends added some more meat to locations (I'm particularly fond of the Great Wall loresheet that let you make up interesting histories for different sections while you're fighting on them: classic!), but LotW was more concerned with the dramatic and thematic dimensions of locations, less with their actual terrain.

For Legends, this was because tactics were centered around narrative keywords, not environmental interaction mechanics. Its a perfectly viable approach; Fate uses this approach too.

But environmental interaction was a keystone of our design (the Effect chart is the central pillar of this design philosophy). The wonderful thing about the chart is that it allows us (and GMs) to create a description of an area (in the case of this Lore, the Vajra Lotus stronghold-temple) and then use the rules selectively as it is interacted with to create its tactical dimension. Just how sturdy are those gigantic walls? How much punishment can that crystal lotus take? GMs make the call on the fly, take a note, and add the tactical infinity to the area in an imminently gameable fashion. Sweet.

The actual game-effect of things like the cloning chambers and gene-therapy labs are clear and gameable, adding a new dimension to the game when they're introduced. Its my hope that, with the toolbox mechanics we've built into the system, inclusions of entries like this encourage GMs to add a gameable dimension to the things they introduce into their own games.

Finally, the leadership and membership of the organization is detailed. Because our character sheets only consist of a few dense elements, we don't have to waste a lot of word count on stat blocks (thank god). The degree of a character gives you the number of techniques they have, their action pool, focus, health, skill masteries... Nearly everything.

Also, our minion rules are a touch more robust and comprehensible than previous editions. I really want people to use minions, so they're balanced to present a challenge to "proper" characters. I was a little underwhelmed by the LotW minions (they were nearly a joke, going last and rolling so few dice, possessing a total lack of interaction with the kung-fu mechanics, etc.). These guys even get special moves (although they're just retreads of the "proper" versions of the earliest kung-fu moves. I like to think of them as the most fundamental forms that characters master on their way to achieving enlightenment)

Wrapping up, we've got the minor dharma and zui consequence list. These are a crack, so I'm going to dig into them a bit while I've got you here.

The XP-mechanism of this game is the Dharma mechanics. Characters get two varieties; greater Dharma, which is picked from a list of big-deal destinies at character creation, and minor Dharma, which are hitched up to Lores.

They both share mechanics. When you do (or choose not to do) something that resonates with your destiny, you get some XP (called Kharma). If you do something anathemic to your destiny, you still get Kharma, but get an equal amount of Zui, which is like bad kharma or a looming divine punishment.

There's a list of triggers to give players and GMs an idea of what the destiny is trying to get the character to do, but each xp-action is initiated, negotiated and agreed upon by player and GM on a case-by-case basis (guidelines for this conversation are helpfully included, of course)

Minor Dharma tie into an organization's goals; you directly link your conduct to their reputation and goals when they agree to train you (or serve as am embarrassment to them if you steal their secrets).

If you're upstanding and act to further their goals, you get Kharma. If you're a jackass and screw up their plans, you get some well-deserved Zui punishment (I like to think of it as "learning the hard way")

(There's a mechanic that needs a touch longer to cook, which relates your conduct to your standing in the organization, but you probably won't see it before the second part of the quickstart)

Zui sits on your character sheet as a resource for the GM to spend. They have a shopping list handily provided to them by your Lores that they can purchase from with Zui. It contains enemies, misfortune, annoyances, and other delightful disasters to rain on your character's head for taking the easy, sinful path.

(Also, GMs are not restricted to this list to introduce challenges into the game. This isn't Dungeon World; GMs can make a lot of this stuff happen as a result of play. But THIS lets them justify it as a pure manifestation of your earned bad luck)

Note that, they don't have to spend Zui earned from a given Lore on that Lore's Zui Consequence list; they can spend it on whatever Lores you've entangled yourself with. kharma pans out in all sorts of unexpected ways!

.....

Well that's our teaser! David's sent the text off to the editor, says it should be done about mid-next month. He and Victor Andrade, our graphic designer (and many-hat-wearing co-game designer and author) are looking at different layouts this month as well. So, happy holidays to all, and we'll see you next year, when we take the kung-fu RPG world by storm!