Here's my gem, the Effect Chart:

You're going to notice a lot of similarity here to this old thing:

And indeed that's the origin of the Effect Chart. The design behind both is rooted in same goal; to allow the modeling of superheroic effort in a game that otherwise cleaves closely to reality.

There are a few elements of this worth explaining in detail:

-The same mechanic for attacking and defending is used for all effort. This allows you to roll your action pool once, and have that roll express the sum total of a character's capabilities in that round. It also gives you tons more options per roll.

-Every character can perform every skill. The seven skills are Power (physical strength and leverage) Finesse (dexterity, agility, and speed) Endurance (toughness and stamina) Senses (environmental awareness and attention to detail) Intellect (skill, depth and speed of thought) Heart (charisma, social adaptability) and Spirit (psychic and spiritual awareness and control).

-The chart determines what effect a skill roll of a given rank can do. It gives both players and GMs a clear idea of the outcome of a (skill) action of (given rank). This works in two directions, both great:

1. Without needing to numericize their prep, a GM can make an on-the-spot call for the difficulty of an action "That boulder? About as heavy as a car, so that's Power Rank 4 to lift"

2. It benchmarks the effects of physical phenomena. "That boulder? About as heavy as a car, so that's a Rank 4 environmental crushing effect as it falls on you"

-Because the math behind the action pool exponentially favors multiple low-rank sets over higher ones, the path to climbing the effect chart is with roll modifiers. The system has two (broadly): Masteries, which give a flat, free +1 rank to actions of a particular skill, and Siddhis (your kung-fu techniques), which increase an action by a number of ranks for a cost in Prana. This means that higher-ranked actions (which have a bigger impact) rely indirectly on capability or magic.

-The chart is also capped from raw rolls; the highest a purely mortal roll can accomplish is Rank 6, which is about what I peg spiderman could do on a good day. Higher effects must be breached with more powerful techniques (Low-levels open rank 7, while the grand master techniques allow any result to be achieved), making the crazy DBZ-stuff an outgrowth of magic.

-It allows a GM to say "you can do what a person can reasonably do" as a shorthand for interaction with the tactical infinity, but it *also* allows them to say "You can do crazy DBZ stuff if you roll high enough", which puts pretty much any Shonen (Bleach, Naruto, DBZ...) on the table. It effectively allows this engine to work like the logic of Shonen, putting "normal person, but can become superhuman" fully on the table.

The chart does more than all of this, but these things are extremely important. I could probably run the game with just the action pool, health, focus, and this chart. But of course, what would magical space kung-fu be without the kung-fu? Next time I'll explain some of the development of Lores and the Siddhis that call them home.

Thursday, November 23, 2017

Tuesday, November 21, 2017

Tripitaka, the Monkey King, and the Robots

Here are those character sheets I promised!

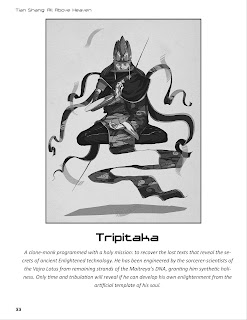

Tripitaka

Tripitaka

There's that wonderful Grobelski piece, plus a little splash-intro to the character. I tried to keep in punchy, but to give a definite direction to a player picking this up for the first time.

Here you're seeing what a character sheet looks like on the table. It's meant to be functional; the empty circles are places that you literally place dice after you roll them, or save then in the focus slots. You're meant to write health in the health boxes. The pools of Prana are meant to have tokens placed in them (glass beads were used in the in-house playtesting). You're also getting a peek at the advancement system as well; again, those empty spaces are meant to be filled with tokens, dice, or writing at the player's preference.

Here's our current layout for the Siddhis and Gupt Kala sheet (your special kung-fu techniques). these are tied to advancement; as you learn newer, more powerful techniques, your overall power level increases, resulting in more action dice, focus slots, and accessible chakra. The empty areas under "power" are meant to contain either the rules text of the technique, or a brief summary and page number for ease of reference.

Sun Wukong

The Robot (Sentry)

The sentry here doesn't have a character sheet, but it's still laid out in such a way as to be functional if printed and placed on a table during a game. A big part of the strategy of this game relies on players being able to see what the bad guy's resources look like (this is often referred to as "system transparency"). What it's action pool has rolled, what it's saved in focus slots, how much Prana it has and will get in future rounds, and how much damage it's taken are all big and clear, so that players can gain familiarity with the strategic elements of gameplay from the quickstart.

Monday, November 20, 2017

Excerpt and art from Tian Shang

Hello everyone! Well it's finally happening: we're gearing up for the release of the Tian Shang quickstart. Since I've busted my keister on it (and since I'm impatiently waiting for everything to finalize) I wanted to share some early draft excerpts with y'all.

The Art

Let me start with the art. This is our chapter-header for act 1. For the quickstart, you're going to see this on the cover. What I love about RPG art, beyond it's "eyecatch" quality, is that it gives a GM the ability to point to something and say "That! You're fighting that"

What you're seeing expertly depicted (by the immeasurably talented Christof Grobelski) up there is the first fight scene with the two pregens Sun Wukong and Tripitaka. Yes, that sentry is your first opponent, and yes, you can smash it with Monkey's Ruyi Jingu Bang (the huge red club: it changes shape!) or adhere one of those holographic demon-sealing strips to it.

The Quickstart

We jump right into it! Bam, you're a clone! Bam, get the monkey king! Bam, scale that mountain! Bam, fight that robot! Wait I'm skipping ahead. You can also see one of the Arik Ten Broeke's suggested additions to the text here; that little callout box for gaming on the internet.

(For those not in the know, Arik was one of the brilliant designers of Legends of the Wulin)

The core mechanics of the game start getting introduced here. I'm particularly fond of the little d10 images I made up there; they're adorable.

The core mechanics, as you'll note, have a lot in common with Legends in terms of how you roll and score dice. You roll your action pool's dice (in this case 4d10) and match them into sets of same-numbered dice. The more same-facing dice in a set, the more powerful the action.

Just like Legends, rolling more than one set allows you to take more than one action in a turn. I greatly admired this rule; it had the dual advantage of empowering players with strategic choice and empowering their characters with lightning-fast flurries of action.

A recurring theme of my work in the mechanics has been just polishing already-genius things like this and making them just a squinch more defined.

You're also seeing a taste of the Effect chart from later in the book. This thing was the core of my new contribution to the system, and I'm just aching to talk about it, but I'm going to shut up until you can see the whole thing (dammit).

One of the things I wanted to do here was demonstrate to GMs how to frame success and failure in terms of an ongoing game. In a less linear module, I would have allowed a failure state ("You don't manage to climb the rocks, and must find a new way up...") but here I'm happy to take the advice of Vincent Baker and Luke Crane and just "fail them forward". It's important to have plenty of techniques in your bag of GM tricks.

Another important thing kept from Legends is the "Chi Imbalance" mechanics (here simply Imbalances). Again, the framework of the mechanic is identical: you have an injury, and choose between manifesting it with a mechanical penalty or with a limitation on your character's described actions.

Where I polished this is small, but important. First, you "lock in" either of the ways of dealing with it at the start of each of your turns. This allows you flexibility over a battle, but forces you to commit to only one approach in a given turn (this set predictability makes strategy easier for both you and your foes, greatly speeding up play).

Second, the descriptive dimension is given a thorough treatment on the next few pages under "Reaching into the Tactical Infinity". This gives GMs and players a framework for using their descriptions to interact with the game world in a non-mechanical way, that doesn't intrude on or devalue the mechanics. Rather, it frames the narration as an equal partner to the mechanics. The Effect Chart helps this as well, but all in due time my pretties.

A few new mechanics are introduced here; the health track and initiative bidding.

I went back to the well of Weapons of the Gods and used their health track. This was in response to complaints that in LotW that you didn't really seem to "damage" your foe, just add an ever-increasing amount of "ripples" (dice that could generate chi imbalances). I fused both mechanics, since I liked elements of both, and created a health track that causes Imbalances as you become more wounded. This created multiple paths to defeat, which added an interesting dimension to combat strategy.

The initiative bid is a predecessor to the initiative roll of LotW. Rather than a single round of bidding, I wanted characters to have to strategize their turn from their initial roll (you only roll once per turn in this system) so I allowed them to continue upping the initiative bid as high as they want with multiple rounds of bidding. It sounds time-consuming, but it typically resolves in just a handful of seconds.

It's drawn some criticism, but I like the bid. Going before an opponent has the effect of changing their dice from offensive vectors to defensive ones, giving you greater control over the rhythm of the battle. Its a sizeable advantage, but balances nicely with saving your dice to have a greater, if slower, impact in the round.

There's that callout box. I've been a firm believer in the shared mindspace and tactical infinity since I became aware of their existence. There's another dimension to RPGs which isn't discussed here, the conversational dimension, which is wonderfully expanded on by Jenna Moran in her games, most notably in Chuubo's Marvelous Wish Granting Engine. Its a bit effervescent, but I haven't read a game closer to the bleeding edge of modern game design.

The river returns here as Focus Slots. The principle is the same; you store dice from this round to use in later rounds. There's also a clarification of how many dice it requires to act in a round (you can do a single action with a single-die set, and you can perform "bonus actions" with sets of 2 or more).

You also get to dip your toes into Chakra, Prana, etc. this round. This is our resource system; chakras give you prana, you spend prana to do magic stuff.

Some really cool stuff here. There's a demonstration of using a Focus slot to "hold" an action between rounds (like holding your breath, lifting heavy stuff, or grapples), which is an innovation I'm really proud of. We also introduce the Gupt Kala ("Shadow Arts") which are our answer to the Secret Arts from the previous games.

Our combat pacing mechanic gets introduced here too. You can open up more of your chakra during a fight, but it takes a set. This allows players to invest in future rounds at a cost to current ones. It also incentivizes them to open as many as they can, since Siddhis (your kung-fu techniques) "cheat" the rolling curve by allowing sets to increase over what's likely to be rolled.

This is the wrap-up of our introduction. Since I didn't want to assume the outcome of the battle, there's a sidebar in there for if the player loses. An important lesson from this introductory fight is that losing doesn't have to mean dying; there's a mechanic in the full rules for introducing death into a scene; its very explicit and transparent. This is my take on a similar rule, the "death box", from Tenra Bansho Zero.

We also introduce the second playable pregen, Sun Wukong, affectionately called Monkey by the design team.

Taking a page from my college texts, I re-introduce and examine concepts here that have been previously introduced, allowing the player and GM to become familiar with them through repetition.

That's all for now folks! Next time, I'll let you take a gander at the bad guy and the pregens, as well as the much-anticipated Effect Chart. Stay tuned!

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)